Meridians V Info

Blog post description.

11/25/202516 min read

Spices has been in use for centuries both for culinary and medicinal purposes. Spices not only enhance the flavor, aroma, texture and color of food and beverages, they also protect us from acute and chronic diseases. There is now ample evidence that spices possess antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antitumorigenic, anticarcinogenic, and glucose- and cholesterol-lowering activities as well as properties that affect cognition and emotions. Research over the past decades has reported on the diverse range of health properties which they possess via their bioactive compounds, including sulfur-containing compounds, tannins, alkaloids and phenolic diterpenes, especially flavonoids and polyphenols. Spices such as clove, turmeric, ginger, fenugreek and cinnamon are excellent sources of antioxidants with their high content of phenolic compounds. Having said that, the key role of spices is in the maintenance of good health [1,2]

Incorporating the right combination of spices and with the optimal Meridians processes, can significantly contribute to heart health and provide various health benefits, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and cholesterol-lowering properties [3]

Spices has a traditional history of use, with strong roles in cultural heritage, and in the appreciation of food and its links to health. Demonstrating the benefits of foods by scientific means remains a challenge, particularly when compared with standards applied for assessing pharmaceutical agents. Pharmaceuticals are small-molecular-weight compounds consumed in a purified and concentrated form. Food is eaten in combinations, in relatively large, unmeasured quantities under highly socialised conditions. The real challenge lies not in proving whether foods, such as spices, has health benefits, but in defining what these benefits are and developing the methods to expose them by scientific means [4,5]. During Meridians processes, not only to ensure no heavy metals, bacteria/pathogen, it is also key to ensure the boiling temperature, pressure used, fermentation processes are according to our strict control and management, providing the optimal and effective approaches to support our body systems.

Ref:

Indian Spices for Healthy Heart - An Overview by Hannah R Vasanthi 1,*, RP Parameswari 1 PMCID: PMC3083808 PMID: 22043203 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3083808/#sec3

USC-UCLA Joint East Asian Studies Center. Along the Silk Road, people, interaction & cultural exchange. http,//www.isop.ucla.edu/eas/sum inst/links/ silkunit.htm . 1993.

Parry JW. New York: Chemical Publishing Co; 1953. The Story of Spices. [Google Scholar]

Turmeric, Pepper, Cinnamon, and Saffron Consumption and Mortality Journal of the American Heart Association Volume 8, Number 18 https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.119.012240

Health benefits of herbs and spices: the past, the present, the future

Article in The Medical journal of Australia · September 2006 Source: PubMed

SAFFRON

Saffron is harvested from the crimson stigmas of C. sativus, a sterile triploid plant that is believed to have originated through selective breeding of wild C. cartwrightianus in ancient Greece (1). Each flower yields only three stigmas, which increases the labor and cost requirements associated with saffron harvesting. Phytochemical analyses have identified four major bioactive constituents of saffron, of which include crocin, crocetin, picrocrocin, and safranal.

Saffron can suppress the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin 1β (IL-1β), and IL-6 by inhibiting nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB signaling) [3].

These anti-inflammatory effects have led researchers to investigate the potential utility of saffron for the management of arthritis, atherosclerosis, and inflammatory bowel disease. The efficacy of saffron against chronic, age-associated cardiovascular and kidney diseases is also being explored [1].

Saffron enhances hippocampal neurogenesis and inhibits β-amyloid aggregation, a key risk factor in Alzheimer's disease (AD) development and progression [2]. Crocin may also improve synaptic plasticity and mitochondrial function in neuronal cells, further supporting cognitive health.

In one study, researchers concluded that saffron extracts and donepezil, a clinically prescribed anti-dementia medication, exhibit similar clinical efficacy, which highlights the potential utility of saffron as a neuroprotective nutraceutical [4].

Saffron, at pharmaceutical doses, may affect cardiovascular disease through several mechanisms [5]. Saffron extract (10, 20, 40 mg/kg per day for 5 weeks) decreases systolic blood pressure in rats [6]. Heat shock proteins are expressed in atherosclerotic plaques, and antibody titers to some heat shock proteins indicate the severity of cardiovascular disease [7]. Saffron decreases anti‐heat shock protein‐27 and anti‐heat shock protein‐70 levels significantly in patients with metabolic syndrome [7].

In summary, based on the researches, some of the key benefits of Saffron are [8]

1. Anti-inflammation- Inhibit cancer growth, arthritis, atherosclerosis, kidney & cardiovascular diseases and inflammatory bowel disease.

2. Support cognitive health.

3. Neuroprotective nutraceutical with anti-dementia.

4. Regulated blood pressure

5. Support cardiovascular health by decreasing anti-heat shock proteins.

Ref:

Mohtashami, L., Amiri, M. S., Ramezani, M., Emami, S. A., & Simal-Gandara, J. (2021). The genus Crocus L.: A review of ethnobotanical uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. Industrial Crops and Products, 171, 113923. DOI: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113923, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0926669021006877?via%3Dihub

Lopresti, A. L., & Drummond, P. D. (2014). Saffron (Crocus sativus) for depression: A systematic review of clinical studies and examination of underlying antidepressant mechanisms of action. Human Psychopharmacology, 29(6), 517–527. DOI: 10.1002/hup.2434, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hup.2434

Moshiri, M., Vahabzadeh, M., & Hosseinzadeh, H. (2014). Clinical Applications of Saffron (Crocus sativus) and its Constituents: A Review. Drug Research, 65(06), 287–295. DOI: 10.1055/s-0034-1375681, https://www.thieme-connect.de/products/ejournals/abstract/10.1055/s-0034-1375681

Akhondzadeh, S., Shafiee Sabet, M., Harirchian, M. H., Togha, M., Cheraghmakani, H., Razeghi, S., Hejazi, S. S., Yousefi, M. H., Alimardani, R., Jamshidi, A., Rezazadeh, S.-A., Yousefi, A., Zare, F., Moradi, A., & Vossoughi, A. (2009). A 22-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind controlled trial of Crocus sativus in the treatment of mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Psychopharmacology, 207(4), 637–643. DOI: 10.1007/s00213-009-1706-1, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00213-009-1706-1

Rameshrad M, Razavi BM, Hosseinzadeh H. Saffron and its derivatives, crocin, crocetin and safranal: a patent review. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2018;28:147–165.

Imenshahidi M, Razavi BM, Faal A, Gholampoor A, Mousavi SM, Hosseinzadeh H. The effect of chronic administration of saffron (Crocus sativus) stigma aqueous extract on systolic blood pressure in rats. Jundishapur J Nat Pharm Prod. 2013;8:175–179.

Shemshian M, Mousavi SH, Norouzy A, Kermani T, Moghiman T, Sadeghi A, Ghayour‐Mobarhan M, Ferns GA. Saffron in metabolic syndrome: its effects on antibody titers to heat‐shock proteins 27, 60, 65 and 70. J Complement Integr Med. 2014;11:43–49.

Saffron’s Evolving Place in Modern Medicine - From Tradition to Evidence

By Hugo Francisco de Souza. Reviewed by Benedette Cuffari, M.Sc.

CLOVE

Clove (Syzygium aromaticum) is one of the most valuable spices that has been used for centuries as food preservative and for many medicinal purposes. Clove is a median size tree (8-12 m) from the Mirtaceae family native from the Maluku islands in east Indonesia [1]. Clove represents one of the major vegetal sources of phenolic compounds as flavonoids, hidroxibenzoic acids, hidroxicinamic acids and hidroxiphenyl propens. Eugenol is the main bioactive compound of clove, which is found in concentrations ranging from 9 381.70 to 14 650.00 mg per 100 g of fresh plant material[2]. With regard to the phenolic acids, gallic acid is the compound found in higher concentration (783.50 mg/100 g fresh weight).

Ref

Clove (Syzygium aromaticum): a precious spice Diego Francisco Cortés-Rojas 1,2,*, Claudia Regina Fernandes de Souza 1,2, Wanderley Pereira Oliveira 1,2 Reviewed by: Marcos José Salvador1,2 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3819475/

Neveu V, Perez-Jiménez J, Vos F, Crespy V, du Chaffaut L, Mennen L, et al. et al. Phenol-Explorer: an online comprehensive database on polyphenol contents in foods. doi: 10.1093/database/bap024.

Shan B, Cai YZ, Sun M, Corke H. Antioxidant capacity of 26 spice extracts and characterization of their phenolic constituents. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53(20):7749–7759. doi: 10.1021/jf051513y.

Pérez-Jiménez J, Neveu V, Vos F, Scalbert A. Identification of the 100 richest dietary sources of polyphenols: an application of the phenol-explorer database. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64(Suppl 3):S112–S120. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.221.

Dudonné S, Vitrac X, Coutière P, Woillez M, Mérillon JM. Comparative study of antioxidant properties and total phenolic content of 30 plant extracts of industrial interest using DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, SOD, and ORAC assays. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57(5):1768–1774. doi: 10.1021/jf803011r.

Halder S, Mehta AK, Kar R, Mustafa M, Mediratta PK, Sharma KK. Clove oil reverses learning and memory deficits in scopolamine-treated mice. Planta Med. 2011;77(8):830–834. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1250605.

Chami F, Chami N, Bennis S, Trouillas J, Remmal A. Evaluation of carvacrol and eugenol as prophylaxis and treatment of vaginal candidiasis in an immunosuppressed rat model. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54(5):909–914. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh436.

Pérez-Conesa D, McLandsborough L, Weiss J. Inhibition and inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes and Escherichia coli O157:H7 colony biofilms by micellar-encapsulated eugenol and carvacrol. J Food Prot. 2006;69(12):2947–2954. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-69.12.2947.

Li HY, Lee BK, Kim JS, Jung SJ, Oh SB. Eugenol inhibits ATP-induced P2X currents in trigeminal ganglion neurons. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;12(6):315–321. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2008.12.6.315.

Ohkubo T, Shibata M. The selective capsaicin antagonist capsazepine abolishes the antinociceptive action of eugenol and guaiacol. J Dent Res. 1997;76(4):848–851. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760040501

Kurokawa M, Hozumi T, Basnet P, Nakano M, Kadota S, Namba T, et al. et al. Purification and characterization of eugeniin as an anti-herpesvirus compound from Geum japonicum and Syzygium aromaticum. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284(2):728–735.

Nam H, Kim MM. Eugenol with antioxidant activity inhibits MMP-9 related to metastasis in human fibrosarcoma cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;55:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.12.050.

Slamenová D, Horváthová E, Wsólová L, Sramková M, Navarová J. Investigation of anti-oxidative, cytotoxic, DNA-damaging and DNA-protective effects of plant volatiles eugenol and borneol in human-derived HepG2, Caco-2 and VH10 cell lines. Mutat Res. 2009;677(1–2):46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2009.05.016.

Ghosh R, Nadiminty N, Fitzpatrick JE, Alworth WL, Slaga TJ, Kumar AP. Eugenol causes melanoma growth suppression through inhibition of E2F1 transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(7):5812–5819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411429200.

However, other gallic acid derivates as hidrolizable tannins are present in higher concentrations (2 375.8 mg/100 g)[3]. Other phenolic acids found in clove are the caffeic, ferulic, elagic and salicylic acids. Flavonoids as kaempferol, quercetin and its derivates (glycosilated) are also found in clove in lower concentrations. Further to research and findings, clove represents a very crucial plant with an enormous potential as food preservative and as a rich source of Antioxidant compounds. In additions, it is also Antimicrobial, Antiviral, Antinociceptive and Anticancer. It's proved biological activities suggest the development of medicinal products for human and animals uses and confirm why this plant has been employed for centuries. [1]

In summary, sharing the following 5 important benefits of Clove:

Antioxidant- Rich source of antioxidants for the treatment of memory deficits caused by oxidative stress. [4-6]

Antimicrobial- Cloves have been found to have strong antimicrobial properties against a number of bacterial and fungal strains including E Coli, Staph aureus and potentially vaginal candidiasis. [1,7,8]

Antinociceptive/Natural pain-reliever- Clove with eugenol support analgesic process, particularly for toothache, join pain and antispasmodic. [9,10]

Antiviral- Clove with eugeniin, a compound isolated from S. aromaticum and from Geum japonicum, was tested against herpes virus strains being effective at 5 µg/mL, and it was deducted that one of the major targets of eugeniin is the viral DNA synthesis by the inhibition of the viral DNA polymerase. [11]

Anticancer- Clove with eugenol inhibits the enzyme MMP-9 which is related to metastasis in human fibrosarcoma cells suggesting its application for prevention of metastasis related to oxidative stress. [12]. In another study, eugenol presented strong genotoxic effects (DNA-damaging) on human VH10 fibroblast, medium genotoxic effects on Caco-2 colon cells and non DNA-damaging effects on HepG2 hepatome cells[13]. Nevertheless the National Toxicology Program based on several long term carcinogenicity studies concluded that eugenol was not carcinogenic to rats. [14]

LEMON GRASS

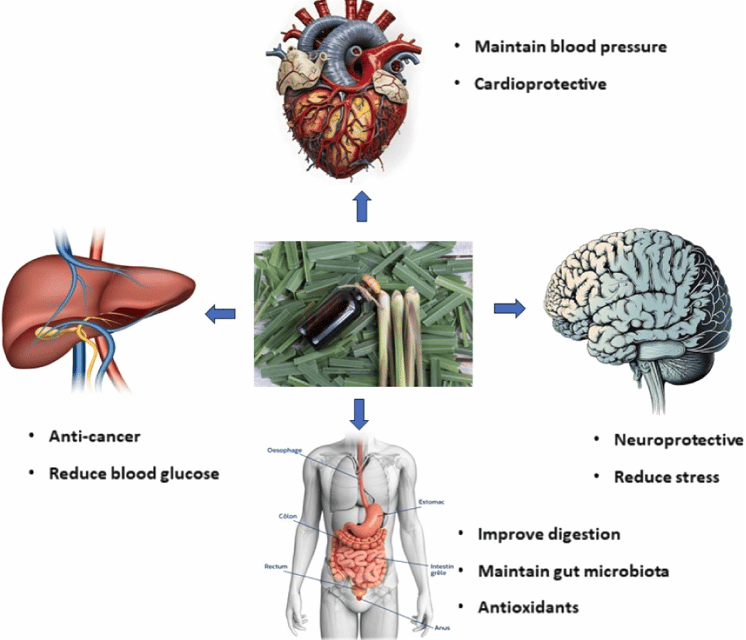

Lemongrass is a tall perennial and fast-growing plant displaying a tuft of leaves that sprout from annulate and sparingly branched rhizomes. It has many bulbous stems that increase the bulk size of the plant as it grows [1], and can reach a height greater than 2 m and a width of around 1 m. [2]. Lemongrass has been employed as a folk medicine in many countries for a variety of purposes. In fact, several biological activities have been reported throughout the years from scientific studies, including antibacterial [9], antifungal [3], antiprotozoal [4], anti-inflammatory [5], antioxidant [6] and anti-carcinogenic activities [6], among others. Given its vast array of applications, it is not surprising that the popularity of lemongrass has increased in recent years, with an increasing number of scientific publications in the last two decades [7]. Several of these publications mention that lemongrass has been used as a folk medicine to lower blood pressure in different countries such as Spain (Canary Islands) [8], Cuba [9-10], Cameroon [11], Egypt [12] and Brazil [13,14,28,29].

Ref:

Shah G., Shri R., Panchal V., Sharma N., Singh B., Mann A.S. Scientific basis for the therapeutic use of Cymbopogon citratus, stapf (Lemon grass) J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2011;2:3–8. doi: 10.4103/2231-4040.79796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Machraoui M., Kthiri Z., Ben Jabeur M., Hamada W. Ethnobotanical and phytopharmacological notes on Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf. J. New Sci. 2018;55:3642–3652. doi: 10.3166/phyto-2019-0160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Wannissorn B., Jarikasem S., Soontorntanasart T. Antifungal activity of lemon grass oil and lemon grass oil cream. Phyther. Res. 1996;10:551–554. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1573(199611)10:7<551::AID-PTR1908>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Pedroso R.B., Ueda-Nakamura T., Dias Filho B.P., Cortez D.A.G., Cortez L.E.R., Morgado-Díaz J.A., Nakamura C.V. Biological activities of essential oil obtained from Cymbopogon citratus on Crithidia deanei. Acta Protozool. 2006;45:231–240. [Google Scholar]

Francisco V., Figueirinha A., Neves B.M., García-Rodríguez C., Lopes M.C., Cruz M.T., Batista M.T. Cymbopogon citratus as source of new and safe anti-inflammatory drugs: Bio-guided assay using lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;133:818–827. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Khadri A., Serralheiro M.L.M., Nogueira J.M.F., Neffati M., Smiti S., Araújo M.E.M. Antioxidant and antiacetylcholinesterase activities of essential oils from Cymbopogon schoenanthus L. Spreng. Determination of chemical composition by GC-mass spectrometry and 13C NMR. Food Chem. 2008;109:630–637. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.12.070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Haque A.N.M.A., Remadevi R., Naebe M. Lemongrass (Cymbopogon): A review on its structure, properties, applications and recent developments. Cellulose. 2018;25:5455–5477. doi: 10.1007/s10570-018-1965-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Darias V., Bravo L., Rabanal R., Mateo C.S., Luis R.M.G., Pérez A.M.H. New contribution to the ethnopharmacological study of the canary islands. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1989;25:77–92. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(89)90047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Carbajal D., Casaco A., Arruzazabala L., Gonzalez R., Tolon Z. OF CYMBOPOGON or Cymbopogon Plant muterials Blood pressure measurement Measurement of diuretic activity Anti-inflammatory effect. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1989;25:103–107. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(89)90049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gómez Y.M., García C.J., Javier A., González D. Caña santa para el tratamiento de ancianos con hipertensión arterial / Lemongrass for treating aged persons with hypertension MsC. Medisan. 2010;14:1061–1067. [Google Scholar]

Dzeufiet P.D.D., Mogueo A., Bilanda D.C., Aboubakar B.F.O., Tédong L., Dimo T., Kamtchouing P. Antihypertensive potential of the aqueous extract which combine leaf of Persea americana Mill. (Lauraceae), stems and leaf of Cymbopogon citratus (D.C) Stapf. (Poaceae), fruits of Citrus medical L. (Rutaceae) as well as honey in ethanol and sucrose experi. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014;14:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Locksley H., Fayez M., Radwan A., Chari V., Cordell G., Wagner H. Constituents of Local Plants. Planta Med. 1982;45:20–22. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-971233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Leite J., Seabra M., Maluf E., Assolant K., Suchecki D., Tufik S., Klepacz S., Calil H., Carlini E. Pharmacology of lemongrass. III. Assessment of eventual toxic, hypnotic and anxiolytic effects on humans. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1986;17:75–83. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(86)90074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Formigoni M.L.O.S., Lodder H.M., Filho O.G., Ferreira T.M.S., Carlini E.A. Pharmacology of lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus Stapf). II. Effects of daily two month administration in male and female rats and in offspring exposed “in utero”. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1986;17:65–74. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(86)90073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

D. Pan, L. Machado, C.G. Bica, A.K. Machado, J.A. Steffani, F.C. Cadoná

In vitro evaluation of antioxidant and anticancer activity of lemongrass ( Cymbopogon citratus (D.C.) Stapf) Nutr. Cancer (2021), pp. 1-15, 10.1080/01635581.2021.1952456

View at publisherGoogle Scholar

M.P. Ngogang, et al. Microbial contamination of chicken litter manure and antimicrobial resistance threat in an urban area setting in Cameroon Antibiotics, vol. 10 (1) (2021), p. 20

G. Sahal, et al. Antifungal and biofilm inhibitory effect of Cymbopogon citratus (lemongrass) essential oil on biofilm forming by Candida tropicalis isolates; an in vitro study J. Ethnopharmacol., vol. 246 (2020), Article 112188, 10.1016/j.jep.2019.112188

O.F. Olukunle, O.J. Adenola Comparative antimicrobial activity of lemon grass (Cymbopogon citratus) and garlic (Allium sativum) extracts on Salmonella typhi

J. Adv. Med. Pharm. Sci. (2019), pp. 1-9, 10.9734/jamps/2019/v20i230104

E.K. Kouassi, I. Coulibaly, P. Rodica, A. Pintea, S. Ouattara, A. Odagiu

“HPLC phenolic compounds analysis and antifungal activity of extract’s from Cymbopogon citratus (DC) Stapf against Fusarium graminearum and Fusarium oxysporum sp tulipae J. Sci. Res. Rep. (2017), pp. 1-11

Toxicological and pharmacological profiling of organically and non-organically cultivated Cymbopogon citratus J. Ayurveda Integr. Med., vol. 10 (4) (2019), pp. 233-240

P.H.O. Borges, et al. Inhibition of α-glucosidase by flavonoids of Cymbopogon citratus (DC) Stapf J. Ethnopharmacol., vol. 280 (2021), Article 114470, 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114470

V. Francisco, et al. Chemical characterization and anti-inflammatory activity of luteolin glycosides isolated from lemongrass J. Funct. Foods, vol. 10 (2014), pp. 436-443

F. Tavares, et al. Cymbopogon citratus industrial waste as a potential source of bioactive compounds J. Sci. Food Agric., vol. 95 (13) (2015), pp. 2652-2659

G. Shah, R. Shri, V. Panchal, N. Sharma, B. Singh, A.S. Mann

Scientific basis for the therapeutic use of Cymbopogon citratus, stapf (Lemon grass)

J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res., vol. 2 (1) (2011), p. 3

C.E. Ekpenyong, E. Akpan, A. Nyoh

Ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry, and biological activities of Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf extracts Chin. J. Nat. Med., vol. 13 (5) (2015), pp. 321-337

S.K. Olorunnisola, H.T. Asiyanbi, A.M. Hammed, S. Simsek

Biological properties of lemongrass: an overview

Int. Food Res. J., vol. 21 (2) (2014), p. 455

Y. Luo, P. Shang, D. Li

Luteolin: a flavonoid that has multiple cardio-protective effects and its molecular mechanisms

Front. Pharmacol., vol. 8 (2017)

Accessed: Feb. 02, 2022. [Online]. Available: 〈https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fphar.2017.00692〉

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S295019972400034X

There are Five key benefits of lemon grass.

Antioxidant- It reduce the oxidative stress induced by rotenone in VERA cells through decreasing ROS levels such as nitric oxide, superoxide, and lipid peroxidation [15]

Antimicrobial effect- It has been shown to have promising antimicrobial ability against numerous microbial strains including Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria spp., Enterococcus faecalis, Salmonella typhi, Candida tropicalis, Fusarium graminearum and Fusarium oxysporum [16-19].

Antidiabetic- Its active constituents such as citral, limonene, and linalool, which showed to lessen hyperglycemia and diabetes-related problems. [20-21]

Anti-inflammatory effect- Its bioactive derivative has been proven to downregulate the proinflammatory factors such as cytokines, iNOS, TNF-α, IL-ß, and IL-6 [22]. In the same context, Fransisco et al. [22] proved that the phenolic acid-rich fraction and tannin-rich fraction inhibits NF-ĸb activation in both human macrophages and murine macrophage pretreated with different C. citratus fractions. [22-25]

Cardioprotective effect- Prevents myocardial oxidative damaged. Its bioactive compound, luteolin inhibits mitogen adenosine map kinase (MAPK) pathway, enhances the cardiomyocytes, ameliorate cardiac function, and prevents cardiac injuries [26-27].

The diversity of C. citratus phytocompounds could be associated with either its ability to counteract free radicals in vitro or in vivo through synergistic effects in decreasing oxidative stress (Fig. 3).

GARLIC

Garlic, besides adding rich flavors in our foods, it also protects our heart. It has long been considered a natural cure for many diseases, especially heart-related ones. It contains a chemical called allicin that lowers blood pressure, decreases cholesterol content in the bloodstream, and promotes better circulation of blood. These properties make it especially useful for lowering the risk of atherosclerosis, which is the hardening of arteries. Garlic, as per a clinical overview, helps with cardiovascular health by decreasing blood pressure and cholesterol, curbing inflammation, and inhibiting dangerous blood clots [1,2]

Ref:

Indian Spices for Healthy Heart - An Overview by Hannah R Vasanthi 1,*, RP Parameswari 1 PMCID: PMC3083808 PMID: 22043203 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3083808/#sec3

5 Indian kitchen spices that can decrease the risk of heart disease

TIMESOFINDIA.COM / Updated: Sep 29, 2025

Rahman K. Historical perspective on garlic and cardiovascular disease. J Nutr. 2001;131:977–979. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.3.977S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fenwick GR, Hanley AB. The genus Allium. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1985;22:199–271. doi: 10.1080/10408398509527415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rahman K, Lowe GM. Garlic and cardiovascular disease, a critical review. J Nutr. 2006;136:736–740. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.3.736S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Abramovitz D, Gavri S, Harats D, Levkovitz H, Mirelman D, Miron T, Eilat-Adar S, Rabinkov A, Wilchek M, Eldar M, Vered Z. Allicin-induced decrease in formation of fatty streaks (atherosclerosis) in mice fed a cholesterol-rich diet. Coron Artery Dis. 1999;10:515–519. doi: 10.1097/00019501-199910000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kleijnen J, Knipschild P, Terriet G. Garlic onions and cardiovascular risk factors. A review of the evidence from human experiments with emphasis on commercially available preparations. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;28:535–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1989.tb03539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yu-Yan Y, Liu L. Cholesterol lowering effect of garlic extracts and organosulfur compounds, Human and animal studies. J Nutr. 2001;131:989–993. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.3.989S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gebhardt R, Beck H. Differential inhibitory effects of garlic-derived organosulfur compounds on cholesterol biosynthesis in primary rat hepatocyte culture. Lipids. 1996;31:1269–1276. doi: 10.1007/BF02587912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ebadi M. The Pharmacodynamic Basis of Herbal Medicine. BocaRaton: CRC Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

Over the centuries, garlic has acquired a unique position in the myths of many cultures as an appalling prophylactic and therapeutic medicinal agent. It has been quoted in the Egyptian Codex Ebers, a 35-century-old document, as useful in the treatment of heart disorders, tumors, worms, bites and other ailments. Hippocrates and Pliny the Elder were both promoters of the intrinsic worth of garlic [3]. The first-century Indian physician Charaka (3000 BC), the father of Ayurvedic medicine, claimed that garlic acts as a heart tonic by maintaining the fluidity of blood and strengthens the heart [4]. Over the last 20 years, this important and exciting role of garlic has been and continues to be confirmed by basic and clinical research reports from around the world.

Allicin, an active compound of garlic showed significantly lowered formation of fatty streaks in the aortic sinus [6]. Kleijnen et al. [7] showed that it also enhance blood fibrinolytic activity. Another in-vitro study shows that water – soluble organosulphur compound S –allyl cysteine present in aged garlic is a potent inhibitor of cholesterol synthesis [8-9]. These findings have also been addressed in clinical trials too.

In summary, the studies point to the fact that garlic helps

Inhibits platelet aggregation,

Reduces blood pressure

Increases antioxidant status [5].

Antiatherosclerosis activity to increase high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels, which may help to remove excess cholesterol from arterial tissue.

Support lipid-and blood pressure-lowering action, as well as antiplatelet, antioxidant, and fibrinolytic effects [10].

CONTACT

A-0-5, Tulin 28, Jalan Riang Ria 8,

Taman Gembira, 58200 Kuala Lumpur

Malaysia

Follow

Connect

info@meridianswell.com

+60 12-201 8658

© 2025. All rights reserved.